At the time of my writing this, it is a quarter to four in the morning. I’m tired, but unable to sleep, and there is nothing too pressing on my mind. Something about that is more frightening. I heard the passing of the train traverse the stilled streets between us just ten or so minutes away (space measured by time), and planes departing from JFK some 13 or so miles from where I lay, low rumblings like mortars that never touch the ground, but grow fainter until gone though you believe the reverberations still echo between the walls.

At the time of you reading this, I cannot say what I’ll be hearing. But I know, that at the time of publication, it will be a quarter to four in the morning and somewhere unknown to you I reside probably lying awake, or else drifting into sleep dreaming of your smiling face.

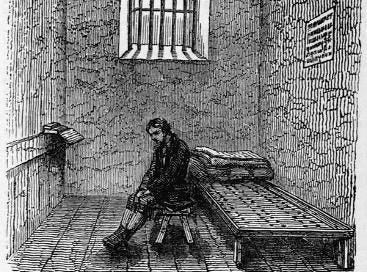

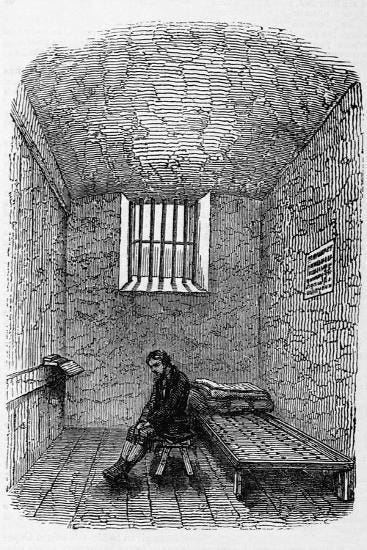

When I initially began this blog (what a dreadful term), the gulag was a metaphorical representation of the political periphery, a pariah in a world I believed I knew best—and to some extent still do. So it is always a shock when a metaphor becomes reality that even now I cannot help but smirk at the tragic-comedy irony of it.

It’s fitting that there should evolve some sort of villain arc, but though it is in my capacity to be dangerous (as all men may be), I am averse to chaos. This is why even in the darkest of places, darkness is methodical, behavior—as with all virtues of societies—is constrained and regulated, and liberty exists everywhere in ordered fashion. To a lesser dramatic degree, you will find that within every arbitrary mess there is familiarity and homeliness—though my books lay scattered about, I know where each one lies.

Chaos is antithetical to the human constitution; and while arbitrary messes are undoubtedly made by man, familiarity is his answer, his excuse, that though things may appear in disarray, he is not dictated in likewise fashion—he has conquered the knowledge of their placements and systematized every thing amongst a heap of stuff. But not all chaos is homely.

In war, we send ordered soldiers to kill and die for the virtue of order and disdain of disorder—we call these morals and immorals. And as with war most times, territory is a measurement of victory, but it itself is least of all the cause; what good is a few hundred miles without the prospect of adopted ideals. Ideals are not established by diktat, unless by diktat we mean quiet and sustained socialization with the corresponding commendation and/or sanctions for some thought and action—the predicates of social capital. Thus it is that commendation and condemnation are ideal-typical responses of a virtuous society, they are ordered responses to an otherwise disordered reality.

So, as with prisons, they are ordered institutions for the disordered. The question of “rehabilitation” lies in the philosophy of the punitive, the end toward which deterrence strives:

It is therefore important to remember that the stain of criminality need not be just or unjust. The purpose is to be unforgettable.

Going back to the “political periphery” for a moment: this is the understructure of conservatism, a collective memory, a methodical inventory of precedence in the practical pursuit of prudence. For all of its wonders and evils. No wonder liberals want to tear you down.

I’ll stop here for now. These ideas are better, if not more conceptually expounded in The Proper Fascist, which I will devote more time to when I’m again staring at my own walls and can again hear the voice of my friend and co-author.

I’m sorry this has become so political. I wrote a short story/prose the other day and found consolation, from the guilt that ensues due to a prolonged respite from writing, in the ego of a man whose thoughts only I can know in their moments.

I guess the truth is that this journalistic entry-writing makes me feel like a schizo. It’s something that I desperately want to stay away from. Novels are easier—you write a story and hide behind its fiction. A good story, or good prose, will make any writer feel really good; but an article or journalism is tranquilizer to the bad writer that can’t admit it—or worse, that doesn’t know it. Hence, “when you think you suck at writing, that’s when you become a journalist.”

Notwithstanding, sometimes it’s necessary to stand bare in front of your world and say, “Here am I.” To the man unafraid of authenticity, bully for you.